Camino De Santiago 2025

- Jean-Paul Courville

- Dec 25, 2025

- 15 min read

Updated: Jan 3

By: Jean-Paul Courville

I finished the Appalachian Trail at the end of 2022 with clarity. I had a vision. A plan. A mindset for what the next chapter of my life was supposed to look like.

Then, I did almost everything I told myself I wouldn’t do.

“Este es el Camino—Mi Camino.”

I was adamant that I wouldn’t accept the first job offer that came along. I told myself to be deliberate—scan industries, be meticulous, rebuild my résumé, aim for alignment instead of urgency. What did I do instead? I accepted the first offer that came along, in a field that wasn’t my strength and wasn’t my background. To be fair, I made an impact. My influence on people was real and meaningful. But technically? I was always playing catch-up—learning industry standards and systems on the fly. That isn’t fair to teammates who are already fluent. I learned a lot, yes. But the cost was constant friction.

Another thing I said that I wouldn’t do was ignore my non-negotiables—especially when it came to relationships or getting into one at all. Well, I got into one anyway. I thought I was wiser. More disciplined. Better at reading the room. I wasn’t. It became toxic. Emotionally draining. Financially damaging. One of the worst decisions of my life.

Then life compounded everything.

After the Appalachian Trail, my mother passed away. A year and a half later, my father was diagnosed with brain cancer.

He passed in July of 2025.

In between those two losses, my body broke down. An old shoulder injury from a fall on the Appalachian Trail finally demanded payment—major shoulder reconstruction and a bicep tendon repair. A few weeks later, I fell from a ladder and ripped my hamstring completely off the bone. Five anchors to reattach. A wheelchair for nearly two months. Arm in a sling for 5 weeks. Then came the humbling process of relearning how to walk.

Somewhere in the middle of grief, surgery, rehab, and exhaustion, I resigned from the job I had taken two years earlier. And here’s the part that messed with my head the most.

I had just come off a successful thru-hike. I was supposed to have it figured out. Instead, I found myself clean-shaven, in a suit and tie, living in a cul-de-sac, commuting an hour each way to a windowless building. I go from wanderlust to wondering WTF?

I felt like a caged animal.

The only thing that gave me relief was imagination—fantasizing about the next adventure. Asking myself what’s next? Revisiting photos and videos from the Appalachian Trail. Reflecting on what I had already done. Reflection doesn’t trap me in the past—it fuels the future. It creates the urge. The urge becomes a plan. The plan becomes movement.

That’s when an old seed resurfaced.

Back in 2011, I watched The Way, starring Martin Sheen, directed by Emilio Estevez—about the Camino de Santiago. That story lodged itself somewhere deep and stayed there quietly for years. After my father’s passing, after settling administrative affairs, after rebuilding my body, stepping away from a job and a relationship that no longer fit, I wrote a memoir of the AT and started my own LLC and I found myself in a rare position.

I had the space.

It wasn’t summer. It wasn’t ideal. It wasn’t the “right” season to go according to the recommended time frame.

But I’ve learned that my life doesn’t move forward when I wait for perfect conditions. It moves when I decide. So I didn’t overthink it.

At the end of October, I stood in Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port, France—registered at the pilgrim’s office, received my credencial—the pilgrim’s passport that would be stamped each day along the way—and handed the scallop seashell that has symbolized pilgrims on the Camino de Santiago for centuries.

I took my first steps along the way.

On the Appalachian trail often we heard “Hike your own hike and the trail will provide”. That was applicable on the Camino.

That didn’t mean disrespecting the Camino or its history. It meant honoring where I was physically, mentally, and emotionally. I had just come off surgeries, grief, loss, and reinvention. I was there to walk, to think, and to listen—to my body and to whatever surfaced along the road.

The Camino de Santiago is a religious pilgrimage—one that’s been walked by pilgrims for more than a thousand years. I chose the Camino Francés, the most traditional route, beginning in Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port and ending in Santiago de Compostela, roughly 500 miles—about 800 kilometers.

This wasn’t a religious pilgrimage for me. That said, in my travels I’ve always been drawn to culture, cuisine, and history, and in many parts of the world—especially Europe, Asia, and Africa—religion is deeply woven into all three. I enjoy immersing myself in those traditions, not to adopt them, but to understand them. I’ve found that approaching experiences with curiosity and an open mind almost always offers something worth learning, especially when that exploration is guided by personal choice and reflection.

I was doing this for a variety of reasons, and if I’m honest, I didn’t fully understand them when I started. Pilgrims talk about being asked the same question along the Camino: Why are you doing it?

What I did know was this—I trusted that the Camino would give me the answers. And it did. Just not all at once.

For me, it was about the physical act of walking again. About community. About meeting people face-to-face, being open to conversation, breaking bread together. Laughter. Stories. And, as I learned quickly, a lot of wine. Vino in Spanish.

There’s a phrase you hear often on the Camino: If there’s no vino, it’s not a Camino. Wine wasn’t just a drink; it was social glue. A pause. A shared moment at the end of a long day. I also made a deliberate decision early on about accommodations. I’ve stayed in more hostels, albergues, and refuges than I can count—across Europe, the United States, and through previous professions. In the military, close quarters were part of life: ships, barracks, deployments. No choice. Limited bathrooms. Tight spaces. You lived where you were told and with whom you were told.

At this stage of my life, I decided I was done with that—unless I had no choice.

If an albergue offered a private room, I took it. If there wasn’t one and a hotel was available, I chose the hotel. If the albergue was the only option in town and meant sharing a dorm like a traditional pilgrim, then that’s what I did.

It became a hybrid approach—practical, intentional, and honest. That was my way.

I needed a place to sleep and, ideally, a private bathroom. Everything else—the dinners, breakfasts, the hikes, the laughter, the conversations—those were the real gifts. And they came regardless of where I laid my head at night.

I chose to walk the Camino from late October through November, well outside the traditional season. And I’d recommend it without hesitation.

There were fewer pilgrims. Fewer bugs. Cooler temperatures. Yes, more rain—but rain has never scared me. What was different was the uncertainty. After November 1st, many places shut down, despite what brochures or websites might say.

More than once, I hiked 17 miles in steady rain, arrived at a village ready to stop—only to find everything closed. No albergue. No hotel. No café. Nothing.

So I pulled out the map and walked another five miles.

Wet. Cold. Mentally taxed.

That kind of moment is a real test. And I’ve experienced versions of it many times in life. The truth is, no matter how often you’ve been there, the initial shock never feels good. But what matters—and what I’ve learned over time—isn’t the shock itself.

It’s the reaction. That’s where experience shows up. That’s where perspective matters. And that’s where the Camino, once again, quietly did what it does best—teach, without preaching.

For 15 minutes each morning before my first step of the day I incorporated pilates movements, mobility work: hips, calves, abductors, lower back, upper body training, and core.

I still managed to repeat one of my classic habits—I carried more than I needed.

I planned to stay in Spain longer than just the Camino, so I wanted options. And, true to form, I finished the journey without wearing half the things I brought. I’ve done this before. I’ll probably do it again. My logic has always been simple: better to have it and not need it than need it and not have it.

Plenty of people disagree—and they’re not wrong. Every ounce matters on a long walk. Extra weight can mean extra suffering. But I looked at this differently. I wanted the weight. I wanted the resistance. I wanted my body to rebuild under something real.

This wasn’t about comfort. It was about strength.

For head and neck protection, I wore a straw cowboy hat. Functional. Familiar. Mine.

Instead of trekking poles—which I absolutely recommend for thru-hikes, elevation, and knee preservation—I carried a single staff. That stick has history.

I found it around 2011 in California and used it across California, Arizona, Utah, and Nevada. After that, it sat in storage for a decade. When I pulled it out, it felt right—like unfinished business. Years ago, I had wrapped the handle tightly with paracord, my handle. I decided this stick would walk the Camino with me, another chapter added to its quiet résumé of places traveled. In the military, my weapon was always with me—an extension of responsibility, awareness, and identity. This stick became something similar. It was part of me. So much so that one morning, when I woke up and couldn’t find it, panic set in. My first thought was that I’d left it at a restaurant. The feeling was immediate and visceral—like I was missing a loved one.

When I realized where it was a few seconds later, I picked it up and embraced it. That might sound strange to some, but it didn’t feel strange to me at all.

My goal wasn’t just to walk from Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port to Santiago de Compostela.

I wanted to go beyond—to the coast. To Finisterre and Muxía. To carry that staff all the way and dunk it into the Atlantic, where the Roman Empire once believed the world ended.

Santiago itself holds deep meaning. The cathedral houses the remains of Saint James, which is why this pilgrimage has drawn people for over a thousand years. That history matters. I respected it deeply.

But like I’ve said, people walk the Camino for countless reasons.

Some reasons are familiar. Some are unexpected. Some are too personal to say out loud.

As for me, the answers didn’t come immediately. They surfaced gradually—

And somewhere along that road, I began to understand why I was really there.

I met some incredible people along the Camino—from all over the world, all ages, all walks of life. That was one of the most compelling parts of the experience. I was genuinely curious about what brought each of them there. Some had seen a movie, like I had. Others had read The Pilgrimage. Some watched a television series back home where the Camino was mentioned in passing. Others grew up in neighboring countries—or in Spain itself—where the Camino was simply part of the cultural lexicon. It was always there. Known. Respected. Everyone had a reason.

Within the first five days, I connected with so many beautiful souls—but many of them were only walking five to seven days. Some felt that was all they needed. Others had a longer plan: one week this year, another week next year, then another, stretching the Camino over four years until it was complete.

What I didn’t expect—at all—was how much I’d struggle with walking on hard surfaces.

Long stretches of asphalt and road, day after day, started to take their toll. I developed a hotspot that turned into a blister, and by the time I noticed it, it was already too late. When I pulled my sock off, the skin on my little toe was nearly gone.

From that point on, it was constant care: bandaging, re-bandaging, limping, experimenting with socks, cutting mileage. For a week and a half, I struggled.

Mornings were still beautiful. Sunrise didn’t come until around 8:30 am that time of year, so I’d eat breakfast, strap on a headlamp, and start walking around 7:45 am. No matter the weather, those early hours were peaceful—almost sacred.

But after one o’clock, the pain hit. I’d soak my feet in cold water whenever I stopped. I’d switch to sandals just to let my foot breathe. And slowly, the joy began to fade—not entirely, but enough that every step required intention.

On November 8th, I arrived at a total of 201 miles thus far. That’s when something clicked.

The 250th birthday of the United States Marine Corps was on November 10th—two days away. My mind immediately went to math. If I walked this many miles on the 9th, and this many on the 10th, I could hit 250 total miles on the 250th birthday of the Marine Corps.

That milestone mattered to me. Because Marines matter. Veterans matter. And too many of us have carried pain quietly, believing strength meant silence. Hitting that milestone on that day wasn’t about ego alone—it was also a moment of reflection. Of honoring those who didn’t make it this far. Those who fought battles long after the uniform came off.

Logic told me it was a bad idea. I was already managing a damaged toe and a worsening blister. The smart move was rest. But ego doesn’t listen well. Stubbornness took the wheel. I pushed hard on the 9th. Then I pushed harder on the 10th. Both days, I left at 3:30 am and On November 10th, I hit 250 miles. And my foot was destroyed.

So destroyed that I had no choice but to take a taxi 18 miles into León. I went straight to a pharmacy, then to a doctor. Treatment. Antibiotics. The next morning, I woke up with a fever.That decision—driven by pride—cost me three full days in León, forced rest, and a hard reminder that even meaningful milestones can demand too high a price when ego outweighs judgment.

And once again, the Camino taught me something—without asking permission.

After a few days of nursing myself and replacing socks, I wasn’t 100 percent—but I was in a good enough place to start walking again. The Camino doesn’t wait for perfect conditions. You either rejoin it, or you don’t. Once back on the trail, I fell into that familiar rhythm again—befriending new people, crossing paths with pilgrims I’d met earlier, then separating and reconnecting days later. That’s one of the subtle gifts of long walks: people drift in and out of your life, sometimes briefly, sometimes meaningfully, always at the right time.

The cathedrals.

Not just Santiago de Compostela at the finish, but places like León and Burgos. Extraordinary architecture. Precision. Scale. Beauty. They inspire on multiple levels—spiritual, historical, artistic—even if you didn’t arrive with religious intent.

Even smaller, lesser-known towns had cathedrals that stopped you in your tracks.

The cultural shifts between regions were noticeable too. Language cadence, food, attitudes—subtle changes that you only really feel when you’re moving through them slowly, on foot, with everything you own on your back. There’s nothing like walking from town to village to city to truly experience a culture instead of just visiting it. I practiced my Spanish when I could. Mostly basic phrases. Polite ones. I worked on pronunciation. Many people spoke English, helped me when I stumbled, and genuinely appreciated the effort when I tried. When I found myself alone with someone who spoke no English at all, we figured it out. That’s where technology earned its keep—ChatGPT became a quiet trail companion. I’d speak in English, translate it into Spanish, show them the screen, and we’d make it work.

There was a lot of laughter.

Body language filled the gaps. Hand signals. Facial expressions. Sometimes comical, sometimes surprisingly precise. Always human. Always kind.

Places like Villafranca del Bierzo stayed with me—especially the climb out of town. That morning, fog sat low in the valley, slowly lifting as the sun broke through, illuminating the village behind me as I moved farther away. Moments like that don’t ask for photos. They just ask you to notice. Long roads stretched out entering and leaving towns—meditative, sometimes brutal, sometimes beautiful. Portomarin, right on the river, became another favorite—quiet, grounding, stunning in its own way.

Then Galicia arrived—and the weather turned. Cold rain. Gray skies. Heavy air.

The climb up O Cebreiro was no joke, but oddly enough, it worked in my favor. Even with a problematic toe, I move better uphill than on flats or descents. While others dreaded it, that climb actually helped me. It came at the end of a very long day—made longer by an accommodation falling through. Another reminder that plans on the Camino are always provisional. This was also where things changed dramatically.

I learned that many pilgrims start in or near Sarria, walking the final 100 kilometers—about 62 miles—into Santiago. That distance qualifies you for the same pilgrim credential as someone who walked from Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port.

For nearly three weeks, we’d seen only a handful of pilgrims each day. After Sarria, the Camino was flooded.

The trail transformed overnight.

And I couldn’t help but wonder—if it was like this in November, I can’t even imagine what summer looks like. But I also ran into pilgrims who had come from far beyond the traditional starting point. Some had hiked from deep inside France or even the Netherlands just to reach Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port. For them, Saint-Jean wasn’t the beginning—it was the halfway point. Roughly 500 miles already behind them before they even started what most people consider the Camino.

I met people who were as thin as rails, hiking 25 to 30 miles a day, machines. Serious mileage. No rest days. Those hikers were fully present. They knew exactly what they were doing, and they were enjoying it on their terms.

One of the most memorable encounters was with a group of gentlemen from Korea. Two of them were slightly older than me and had been best friends for more than two decades. Along the way, they welcomed a 39-year-old fellow Korean who had been hiking alone into their circle.

For the first week of his Camino, his routine was simple and relentless—headlamp on early, walk until sunset, find a place to sleep, read, and repeat.

No lingering. No socializing. Just movement.

When he met these older gentlemen, something shifted. They encouraged him to slow down. To walk less. To sit longer. To see things. To share dinner. To drink a beer. To experience what so many people quietly discover on the Camino—that if you stop forcing it, something will eventually find you. We couldn’t speak the same language, but that didn’t matter. Translation apps filled the gaps over dinner. Laughter did the rest. He had a heart of gold—kind, complimentary, genuine. I liked him a lot.

The morning I walked into Santiago de Compostela, I had about 12 miles left. It was cold. It was raining. And it didn’t bother me at all. I knew I’d get a room. I knew I’d get dry. I knew I’d take a couple of days to celebrate the accomplishment.

But the arrival itself was… underwhelming.

You walk through a modern part of the city before reaching the cathedral. The square was packed—tourists taking selfies, engagement photos, large tour groups following guides waving flags and speaking into microphones. Mixed into all of that were pilgrims who had walked five days from nearby starting points.

Their joy wasn’t the same. Not compared to those who had walked the entire Camino Francés. That difference was visible. Tangible.

So the next morning, before sunrise, I walked back to the cathedral square—alone.

The city was quiet. The bells rang through the empty streets. The sun rose behind the cathedral, backlighting it in a way that felt timeless. Sacred. Undisturbed.

That moment erased the disappointment of the day before.

That was the Santiago I needed.

I highly recommend exploring Santiago de Compostela—it deserves the time. But after two days, I felt the pull again. I wasn’t done walking. The Camino wasn’t finished with me yet. So I turned west.

The coastline was next.

For my final stage, following a recommendation from the pilgrim’s office,

I walked first to Muxía. They explained that Muxía carries a history of death at sea—ships wrecked against the rocks, lives lost to storms and unforgiving coastline. From there, you move on to Finisterre—or Fisterra in Galician—symbolizing life. One represents destruction and endings; the other renewal and continuation.

The weather didn’t cooperate. Rain. Hail. Cold. Wind. But between those hard moments were pockets of extraordinary beauty along the coast—clear skies, dramatic cliffs, waves crashing below. Landscape-wise, this was my favorite part of the entire Camino.

The Romans believed this was the end of the world—Finis Terrae. The world’s edge.

What surprised me most, though, wasn’t the geography.

It was the loneliness.

I’m good alone. I’ve always been comfortable with solitude. But for four and a half weeks—from Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port to Santiago de Compostela—I was surrounded by people. Friends. Fellow pilgrims. Shared meals. Bars. Wine. Laughter. Conversation.

And suddenly, that was gone. I still saw a few pilgrims, but it wasn’t the same. Everyone I had connected with ended their journey in Santiago. This final stretch was quiet. Isolated.

And that, too, was a lesson.

Along the Camino, I learned why I had really come. One of the biggest reasons was forgiveness—specifically, forgiving myself. For not always being the best version of who I know I can be, being an awful person at times. For moments in my life where I fell short with people who mattered. Even knowing the kind of man I strive to be—always trying to do better—I realized I still needed to extend myself grace.

Forgiveness isn’t easy. But I believe I accomplished it.

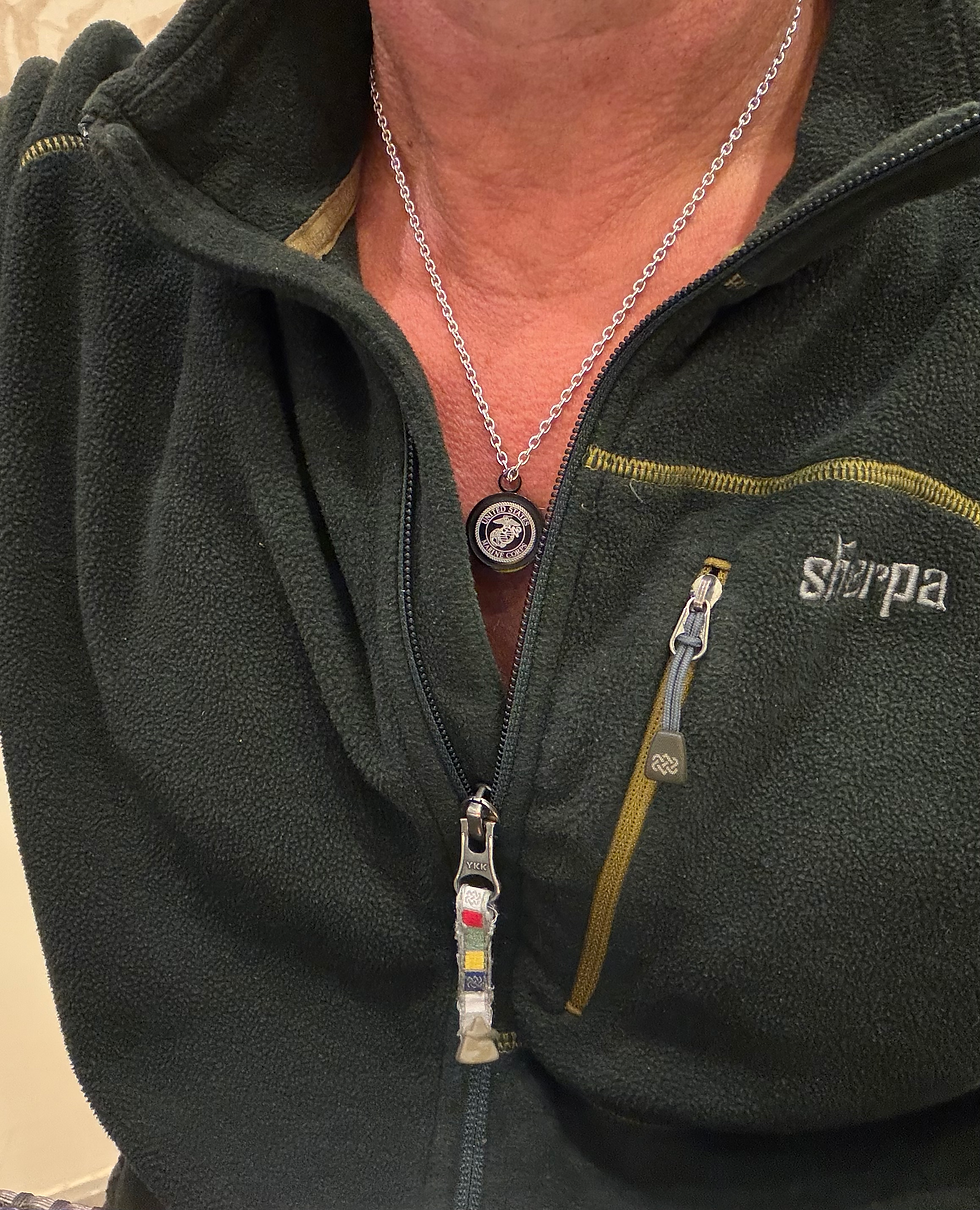

Shortly after my father passed in July, another loss followed. A close friend of mine—Martin Everett—passed away from pancreatitis. He was ten years younger than me and served as my right-hand man in combat in 2003. He lived a troubled life, but I loved him. His family had him cremated and sent me his ashes, encased in a beautifully crafted Marine Corps emblem necklace so I could carry him with me. When people asked, I told his story—but I never forced it. I brought him into countless places, conversations, moments. And eventually, I took him into the cathedral at Santiago de Compostela.

There, I was given a certificate—written in Spanish, stamped and dated November 29th—recognizing that his ashes had been blessed in the cathedral. I framed it and mailed it to his wife. I sent photos to his mother and mother-in-law and shared the story of where he had been and why.

Another beautiful soul worth mentioning.

Her name is Jensen Lewis. I’ve known her since she was 18, when she was a young Navy sailor. She asked me to bring her back a rock from the Camino.

I selected one near Pamplona, and carried it all the way to Cruz de Ferro. Traditionally, pilgrims place a rock there to represent the burdens they’ve carried—then leave it behind and move forward lighter. I placed her rock at the base, then found another—clean and well-shaped, resembling a clean slate, a new beginning—and carried it from Cruz de Ferro to Santiago, and on to the coast. I dipped it into the Atlantic Ocean and mailed it to her.

A symbol of the journey. Of renewal. Of friendship. Of mentorship—

And that’s how the Camino ended for me. With clarity, forgiveness, care, selflessness, and the quiet understanding that sometimes the road gives you exactly what you didn’t know you were asking for.

I left Spain lighter than I arrived—not because I carried less, but because I let more go. And while the Camino ended at the ocean, the lessons it gave me will continue long after the boots came off.

Buen Camino.